A Few Thoughts on the Chevron Reversal

"Resolution of statutory ambiguities involves legal interpretation, and that task does not suddenly become policymaking just because a court has an 'agency to fall back on.'"

Yesterday, the Supreme Court killed off the "Chevron Doctrine." The left, broadly, is not happy with this. Many on the right are pleased. But I think it's worth thinking twice before a victory lap.

Before we get into it, here's a quick TLDR;

Under Chevron, if a law is ambiguous, federal agencies like the ATF or EPA can fill in the gaps with their own "expert" opinions in the form of rules and regulations, and the court system must defer to these opinions except in a small set of circumstances. It's the judicial system's version of "trust the experts."

The Backstory

"Chevron" was borne of the 1984 Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. decision. In this decision, SCOTUS created a framework for courts to follow when ambiguous laws failed to address specific situations that arose after the law was passed.

Chevron implemented a two-step test for courts to follow when reviewing the interpretations of statutes by federal agencies. The test was this:

1. If the statute is clear, follow Congress's intent.

2. If the statute is ambiguous, defer to the agency's interpretation.

The thinking was simple: if Congress's intent with a law is clear, then courts and agencies must follow Congress's wishes. But sometimes, a law passed by Congress does not precisely address a specific situation that arises later on.

When this happens, there are statutory gaps in the law. Federal agencies are responsible for administering and enforcing Congress's laws, so gaps "necessarily require the formulation of policy and the making of rules to fill any gap left, implicitly or explicitly, by Congress." [1]

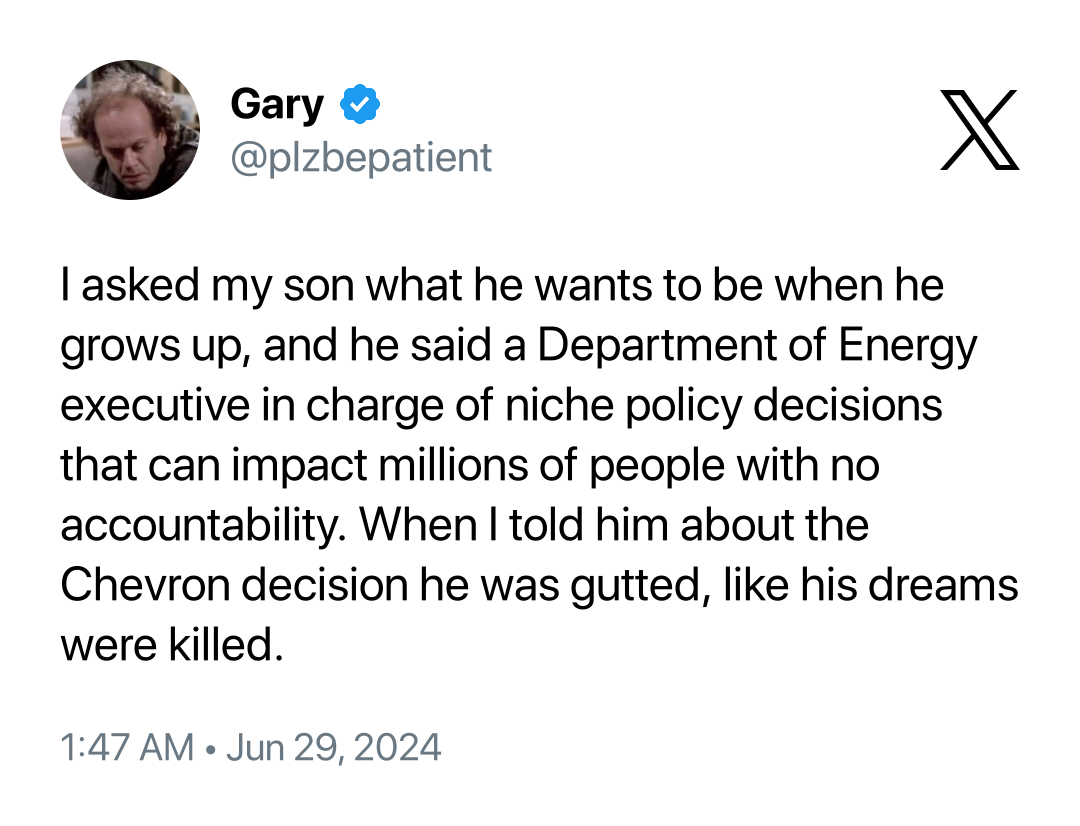

These policies and rules that "fill any gap left" are crafted by federal agencies like the EPA or the ATF. These agencies are helmed by political appointees who serve specific partisan interests; they are not led by elected representatives who are (ostensibly) accountable to voters.

Further, Chevron requires that if "Congress has explicitly left a gap...there is an express delegation of authority to the agency regulation" that is given "controlling weight" unless the agency's Rule is "arbitrary, capricious, or manifestly contrary to the statute." [2]

This basically means that federal agencies can write their own enforcement rules and define (or redefine) their own terms, and courts must defer to these rules unless they are obviously contrary to the law's intent or are arbitrary and capricious.

Chevron is a Swiss army knife. Since 1984, federal courts have cited Chevron in over 18,000 decisions.[3]

To be fair, the overall concept sounds nice. In a good-faith world, it makes sense to defer to a (real) expert when making a decision about something of which you know very little. But as we know, the government rarely acts in good faith.

For example, ATF has repeatedly lost in court after attempting to change the definitions (and, therefore, the legalities) re: firearms equipped with stabilizing braces or bump stocks. Federal agencies can disrupt entire industries by throwing something at the wall and hoping it sticks.

Friday's reversal of Chevron was enthusiastic. SCOTUS saw the Chevron deference as a violation of the 1946 Administrative Procedure Act (APA), which serves as "a check upon administrators whose zeal might otherwise have carried them to excesses..."

From the court's opinion:

"The [APA] requires courts to exercise their independent judgment in deciding whether an agency has acted within its statutory authority, and courts may not defer to an agency interpretation of the law simply because a statute is ambiguous; Chevron is overruled."

And so – boom – Chevron is dead.

Highlights from the court's opinion:

- "Article III of the Constitution assigns to the Federal Judiciary the responsibility and power to adjudicate 'Cases' and 'Controversies'"

- "Chevron cannot be reconciled with the APA by presuming that statutory ambiguities are implicit delegations to agencies. That presumption does not approximate reality."

- "Perhaps most fundamentally, Chevron’s presumption is misguided because agencies have no special competence in resolving statutory ambiguities. Courts do."

- "Finally, the view that interpretation of ambiguous statutory provisions amounts to policymaking suited for political actors rather than courts is especially mistaken because it rests on a profound misconception of the judicial role."

- The court DID specify that it "does not call into question prior cases that relied on the Chevron framework." So, old cases are grandfathered in.

My personal thoughts on this:

1) Chevron is a good rule to have if you are in power. It gives your political allies and appointees more sovereignty and affords them the capacity to end-run the legislative and judicial branches.

2) It makes sense to me that questions of law be decided by courts rather than bureaucrats. The "experts" at the ATF and the EPA are rarely experts in the word's legacy definition.

3) If Trump wins the 2024 election, the reversal of Chevron may be remembered as a conservative Supreme Court stepping on a rake. The void of a suddenly gone Chevron doctrine will be filled by progressive NGOs DDOSing the court system with an endless stream of semantic lawsuits.

4) Overall, the reversal of Chevron will make the executive branch substantially less powerful. That's good news if your executive branch is run by a cabal of satanic pedophiles, gay race communists, and cross-dressing kleptomaniacs. But remember that this sword cuts both ways. (Especially if Trump becomes president in 2025.)

Summing up:

If you oppose executive authority as a concept in and of itself, the Chevron reversal is good news. If you see executive authority as a Real ThingTM but ideologically oppose the leftist authority you have been subjected to for the last 40 years, the Chevron reversal may end up being a mixed bag.

The reversal of Chevron restores the federal judiciary to a role more closely aligned with what the founders envisioned. But in a political climate ruled by foreign interests, degenerate freaks, and literal traitors, the change may make it harder for a motivated POTUS to "drain the swamp" decisively.

No blackpills, though. (We're going to win.)

Bonus tweet:

-Lee